My first impression of walking along the section of the Great Wall of China closest to Beijing was disappointment. I don't know what was more detrimental: the drizzling rain, the huge parking lot with buses below, or the crumbling steps, clearly laid by modern builders rather than ancient masters, which were crumbling under the influx of tourists. The weather improved the next day, but my mood didn't improve, as the wall was swarming with tourists. We made several flights, garnered hundreds of surprised glances, and tried to leave this "tourist paradise" as quickly as possible.

A friend of our translator, Elena, suggested an interesting spot on the Wall a few dozen kilometers to the east—Huanghuacheng. He said part of the Wall in this region was flooded by an artificial lake. We arrived there late in the afternoon. Despite a fairly strong wind, we managed to make a couple of flights over the lake in the rays of the setting sun.

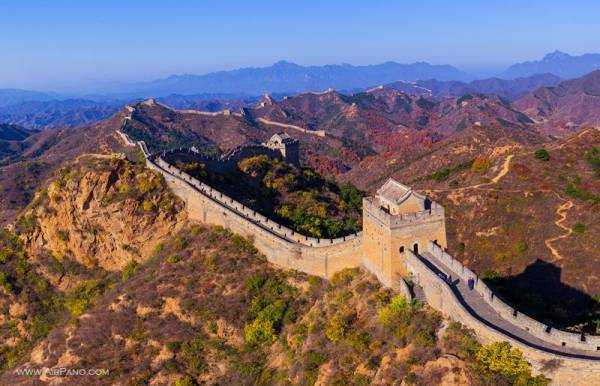

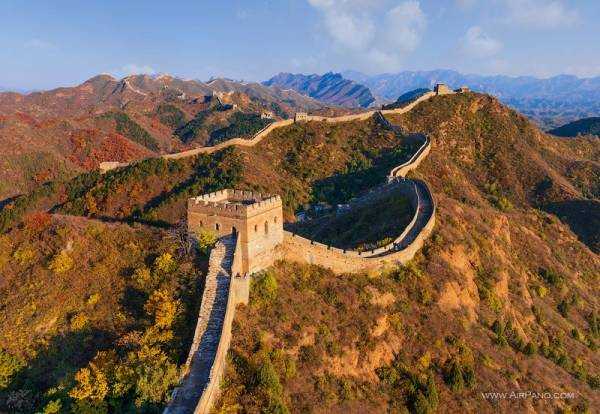

That evening, while processing the footage, I finally realized for the first time what a wonder of the world we were about to photograph—the Wall in the panoramas stretched from horizon to horizon, sometimes descending into crevices, sometimes rising along the ridges of the surrounding mountains. It was beautiful and completely inexplicable how people managed to build such a massive structure.

The next day was spent trying to climb the section of the wall west of the lake. It was closed to tourists, as it had clearly been recently restored. We managed to find a way up – we climbed into one of the towers via a ladder abandoned by the builders. Frankly, the restored section of the wall isn't very impressive; it lacks the spirit of antiquity. A little later, reaching the top of the hill, we saw the old section – without the restored railings, with grass growing between the stones. These sections look, in my opinion, much more interesting, but they're not really suited for mass tourism. Apparently, that's why the Chinese are gradually clearing and improving these areas.

A few days later, on another section of the Wall—Mutianyu—we met a girl from Ukraine. What a brave woman! Irina was hitchhiking alone, speaking no Chinese. She managed to reach China by hitchhiking through Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan. As part of this journey, Irina decided to walk the Wall for several days. The photographs she showed us showed a completely different Wall: dense bushes, crumbling steps, and almost vertical sections that require crawling. It was amazing how this short, frail girl managed to overcome all these obstacles alone, spending the night in the ruins of watchtowers, freezing at night, and suffering from thirst during the day.

After wishing Irina good luck, we became eager to see "the other Wall." Our search led us to two magically beautiful places: Jinshanling and Gubeikou.

Jinshanling's paradoxical beauty is due to several factors. Although restorers and the amenities of civilization have reached this section of the wall (there are several well-maintained trails and a cable car), the restoration has not been comprehensive. Many towers and sections remain untouched. Another factor is the unique mountain topography and, as a result, the Wall's fascinating structure—a true paradise for professional photographers. If you look at a postcard of the Great Wall, chances are you see Jinshanling.

When we arrived at the Gubeikou Wall, located near Jinshanling, I got the impression that the restorers hadn't gotten there yet. Only a few towers had been slightly reinforced with steel strips along their tops, and lightning rods had been installed to reduce the impact of lightning strikes.

In my opinion, this is the most meditative section of the Wall. Distance and time flow here somehow differently than in the world we're used to. There's no rush, no fuss. You walk, seemingly slowly, but the kilometers slip away unnoticed. There's no fatigue, as there are almost no steps here. You walk along a grassy path, through dilapidated sections of the Wall, where its interior can be examined in minute detail. One tower, a second, a third... It's very difficult to stop. At some point, we catch ourselves wanting to go on and on, without stopping. But the sun is quickly beginning to set, and it's time for us to return to the village where we left our car and driver.

This trip wasn't without its share of luck. One day, we left Beijing for a shoot in Badailing, one of the Wall's most popular tourist spots. I wasn't expecting much beauty from this shoot, but I was still very disappointed when it turned out we'd chosen the wrong location: we were supposed to watch the sunset on a different mountainside, which we'd never reach in time. The sun had set, and we went to dinner at a local restaurant. Imagine our surprise when, upon stepping outside, we saw the Wall illuminated for the night! It's only turned on for holidays! However, as we learned from security, an important official was visiting the Wall that day, and the lights had been turned on for him. Naturally, we decided to take off! And we have to hand it to the local security guards—even though the VIP had already left, they kept the floodlights on until our flights were over.

We decided to spend our last day in China at our favorite spot, Jinshanling. The weather wasn't ideal, so the helicopter stayed in the car. Dima shot panoramas, and I simply wandered around, looking for interesting angles for Instagram. We stopped by the Main Tower—we hadn't been there on our last visit because that section of the wall was closed for filming. Next to the tower, we found a small shop selling photography and coffee. After leafing through the books and looking at the clerk, I was surprised to discover that the man standing before us was the photographer himself, Zhou Wanping. Mr. Zhou is a self-taught photographer who lives in a nearby village. He is famous for his photographs of the Wall, taken at different times of the year and winning numerous prizes in international competitions. After admiring the winter views of the wall and receiving an autograph from the photographer as a souvenir, we leisurely walked toward the park exit.

And although on the first day of filming I couldn’t even think about it, on the way to the car the thought kept going through my head that I didn’t want to leave, and maybe I’d come back here again…

Now let's tell you a few facts about the Great Wall of China.

The Great Wall of China is one of those world landmarks about which you can't ask, "What is it?" or "Where is it?"—and not just because the answer is in its name. The Great Wall of China is a renowned monument without equal.

Its construction began in the 3rd century BC: after the unification of China, Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi ordered the construction of a solid wall to protect the northwestern borders of the empire from attacks by nomadic peoples.

The construction of the Wall was not easy. The main problem was the lack of adequate infrastructure for construction: there were no roads, not enough water or food for the 300,000-strong army of workers, and the terrain itself was extremely difficult for such a grandiose structure.

According to the plan, the wall was to run along the mountain range, skirting all its spurs and traversing both high ascents and deep gorges. But it is precisely this, along with its size, that makes the Great Wall of China unique: it blends seamlessly into the landscape, forming a single whole with it.

The first sections were made of clay; later, builders began using stone slabs laid tightly against each other on layers of earth. To hold these pieces together and to control weed growth at the joints between the slabs, the Chinese invented a unique mixture: a mixture of sticky, thick rice porridge and slaked lime. However, this innovative technology drew criticism in southern China, where, by order of the emperor, the entire rice harvest was being exported.

Over its long history, the defensive structure has changed its appearance many times: some sections were destroyed, while others were rebuilt. Today, when speaking of the size of the Great Wall of China, it is common to quote the figure "8,850 kilometers": this is its total length including all its branches. The actual length of this Chinese landmark is 6,259 kilometers, 359 kilometers of which are trenches, and another 2,232 kilometers are natural defensive barriers such as hills and rivers. Meanwhile, according to archaeological research, the Wall was once incomparably longer: 21,196 kilometers in total.

The Great Wall of China averages 6.6 meters in height, although in some sections it is less, and in others it is even more than 10 meters. Along its entire length, casemates and watchtowers are erected for protection, and fortresses are located at the main mountain passes.

In 1987, the Great Wall of China was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, and in July 2007, it was named one of the New Wonders of the World. Over the past decades, the monument has suffered significant damage: sections were demolished to make way for roads and other structures. Weather (heavy rains and sandstorms) and other factors also played a role in the wall's deterioration.

Video: Dan Zimmerman

Sometimes, tragic oddities arise: for example, in one district of Suizhong County, several generations of local farmers spent years building their homes using stones they found in the mountains. Only recently was it discovered that these were the remains of a legendary monument, something previously unknown to both local authorities and archaeologists.

It's commonly believed that the Great Wall of China can be seen from the Moon, or at least from space, from near-Earth orbit. Both these claims are unsubstantiated: even a Chinese astronaut failed to see China's most important (and largest) landmark, and the European Space Agency, determined to prove that the Wall is indeed visible from space, published a photograph to that effect... and embarrassed itself: the image depicted a river.

To film our panoramas, we fly below Earth orbit, allowing you to admire the Great Wall of China in all its glory.

Source: travel.ru